Sponges are animals of the phylum Porifera (/pɒˈrɪfərə/; meaning “pore bearer”). They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through them, consisting of jelly-like mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of cells. Sponges have unspecialized cells that can transform into other types and that often migrate between the main cell layers and the mesohyl in the process. Sponges do not have nervous, digestive or circulatory systems. Instead, most rely on maintaining a constant water flow through their bodies to obtain food and oxygen and to remove wastes.

Sponges are similar to other animals in that they are multicellular, heterotrophic, lack cell walls and produce sperm cells. Unlike other animals, they lack true tissues and organs, and have no body symmetry. The shapes of their bodies are adapted for maximal efficiency of water flow through the central cavity, where it deposits nutrients, and leaves through a hole called the osculum. Many sponges have internal skeletons of spongin and/or spicules of calcium carbonate or silicon dioxide. All sponges are sessile aquatic animals. Although there are freshwater species, the great majority are marine (salt water) species, ranging from tidal zones to depths exceeding 8,800 m (5.5 mi).

While most of the approximately 5,000–10,000 known species feed on bacteria and other food particles in the water, some host photosynthesizing micro-organisms as endosymbionts and these alliances often produce more food and oxygen than they consume. A few species of sponge that live in food-poor environments have become carnivores that prey mainly on small crustaceans.[1]

Most species use sexual reproduction, releasing sperm cells into the water to fertilize ova that in some species are released and in others are retained by the “mother”. The fertilized eggs form larvae which swim off in search of places to settle.[2] Sponges are known for regenerating from fragments that are broken off, although this only works if the fragments include the right types of cells. A few species reproduce by budding. When conditions deteriorate, for example as temperatures drop, many freshwater species and a few marine ones produce gemmules, “survival pods” of unspecialized cells that remain dormant until conditions improve and then either form completely new sponges or recolonize the skeletons of their parents.[3]

The mesohyl functions as an endoskeleton in most sponges, and is the only skeleton in soft sponges that encrust hard surfaces such as rocks. More commonly, the mesohyl is stiffened by mineral spicules, by spongin fibers or both. Demosponges use spongin, and in many species, silica spicules and in some species, calcium carbonate exoskeletons. Demosponges constitute about 90% of all known sponge species, including all freshwater ones, and have the widest range of habitats. Calcareous sponges, which have calcium carbonate spicules and, in some species, calcium carbonate exoskeletons, are restricted to relatively shallow marine waters where production of calcium carbonate is easiest.[4] The fragile glass sponges, with “scaffolding” of silica spicules, are restricted to polar regions and the ocean depths where predators are rare. Fossils of all of these types have been found in rocks dated from 580 million years ago. In addition Archaeocyathids, whose fossils are common in rocks from 530 to 490 million years ago, are now regarded as a type of sponge.

The single-celled Choanoflagellates resemble the choanocyte cells of sponges which are used to drive their water flow systems and capture most of their food. This along with phylogenetic studies of ribosomal molecules have been used as morphological evidence to suggest sponges are the sister group to the rest of animals.[5] Some studies have shown that sponges do not form a monophyletic group, in other words do not include all and only the descendants of a common ancestor. Recent phylogenetic analyses suggest that comb jellies rather than sponges are the sister group to the rest of animals.[6][7][8][9]

The few species of demosponge that have entirely soft fibrous skeletons with no hard elements have been used by humans over thousands of years for several purposes, including as padding and as cleaning tools. By the 1950s, though, these had been overfished so heavily that the industry almost collapsed, and most sponge-like materials are now synthetic. Sponges and their microscopic endosymbionts are now being researched as possible sources of medicines for treating a wide range of diseases. Dolphins have been observed using sponges as tools while foraging.[10]

Distinguishing features

Sponges constitute the phylum Porifera, and have been defined as sessile metazoans (multicelled immobile animals) that have water intake and outlet openings connected by chambers lined with choanocytes, cells with whip-like flagella.[11] However, a few carnivorous sponges have lost these water flow systems and the choanocytes.[12][13] All known living sponges can remold their bodies, as most types of their cells can move within their bodies and a few can change from one type to another.[13][14]

Like cnidarians (jellyfish, etc.) and ctenophores (comb jellies), and unlike all other known metazoans, sponges’ bodies consist of a non-living jelly-like mass sandwiched between two main layers of cells.[15][16] Cnidarians and ctenophores have simple nervous systems, and their cell layers are bound by internal connections and by being mounted on a basement membrane (thin fibrous mat, also known as “basal lamina“).[16] Sponges have no nervous systems, their middle jelly-like layers have large and varied populations of cells, and some types of cells in their outer layers may move into the middle layer and change their functions.[14]

| Sponges[14][15] | Cnidarians and ctenophores[16] | |

|---|---|---|

| Nervous system | No | Yes, simple |

| Cells in each layer bound together | No, except that Homoscleromorpha have basement membranes.[17] | Yes: inter-cell connections; basement membranes |

| Number of cells in middle “jelly” layer | Many | Few |

| Cells in outer layers can move inwards and change functions | Yes | No |

Basic structure

Cell types

A sponge’s body is hollow and is held in shape by the mesohyl, a jelly-like substance made mainly of collagen and reinforced by a dense network of fibers also made of collagen. The inner surface is covered with choanocytes, cells with cylindrical or conical collars surrounding one flagellum per choanocyte. The wave-like motion of the whip-like flagella drives water through the sponge’s body. All sponges have ostia, channels leading to the interior through the mesohyl, and in most sponges these are controlled by tube-like porocytes that form closable inlet valves. Pinacocytes, plate-like cells, form a single-layered external skin over all other parts of the mesohyl that are not covered by choanocytes, and the pinacocytes also digest food particles that are too large to enter the ostia,[14][15] while those at the base of the animal are responsible for anchoring it.[15]

Other types of cell live and move within the mesohyl:[14][15]

- Lophocytes are amoeba-like cells that move slowly through the mesohyl and secrete collagen fibres.

- Collencytes are another type of collagen-producing cell.

- Rhabdiferous cells secrete polysaccharides that also form part of the mesohyl.

- Oocytes and spermatocytes are reproductive cells.

- Sclerocytes secrete the mineralized spicules (“little spines”) that form the skeletons of many sponges and in some species provide some defense against predators.

- In addition to or instead of sclerocytes, demosponges have spongocytes that secrete a form of collagen that polymerizes into spongin, a thick fibrous material that stiffens the mesohyl.

- Myocytes (“muscle cells”) conduct signals and cause parts of the animal to contract.

- “Grey cells” act as sponges’ equivalent of an immune system.

- Archaeocytes (or amoebocytes) are amoeba-like cells that are totipotent, in other words each is capable of transformation into any other type of cell. They also have important roles in feeding and in clearing debris that block the ostia.

Glass sponges’ syncytia

Glass sponges present a distinctive variation on this basic plan. Their spicules, which are made of silica, form a scaffolding-like framework between whose rods the living tissue is suspended like a cobweb that contains most of the cell types.[14] This tissue is a syncytium that in some ways behaves like many cells that share a single external membrane, and in others like a single cell with multiple nuclei. The mesohyl is absent or minimal. The syncytium’s cytoplasm, the soupy fluid that fills the interiors of cells, is organized into “rivers” that transport nuclei, organelles (“organs” within cells) and other substances.[20] Instead of choanocytes, they have further syncytia, known as choanosyncytia, which form bell-shaped chambers where water enters via perforations. The insides of these chambers are lined with “collar bodies”, each consisting of a collar and flagellum but without a nucleus of its own. The motion of the flagella sucks water through passages in the “cobweb” and expels it via the open ends of the bell-shaped chambers.[14]

Some types of cells have a single nucleus and membrane each, but are connected to other single-nucleus cells and to the main syncytium by “bridges” made of cytoplasm. The sclerocytes that build spicules have multiple nuclei, and in glass sponge larvae they are connected to other tissues by cytoplasm bridges; such connections between sclerocytes have not so far been found in adults, but this may simply reflect the difficulty of investigating such small-scale features. The bridges are controlled by “plugged junctions” that apparently permit some substances to pass while blocking others.[20]

Water flow and body structures

Most sponges work rather like chimneys: they take in water at the bottom and eject it from the osculum (“little mouth”) at the top. Since ambient currents are faster at the top, the suction effect that they produce by Bernoulli’s principle does some of the work for free. Sponges can control the water flow by various combinations of wholly or partially closing the osculum and ostia (the intake pores) and varying the beat of the flagella, and may shut it down if there is a lot of sand or silt in the water.[14]

Although the layers of pinacocytes and choanocytes resemble the epithelia of more complex animals, they are not bound tightly by cell-to-cell connections or a basal lamina (thin fibrous sheet underneath). The flexibility of these layers and re-modeling of the mesohyl by lophocytes allow the animals to adjust their shapes throughout their lives to take maximum advantage of local water currents.[22]

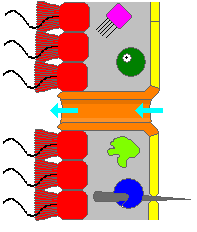

The simplest body structure in sponges is a tube or vase shape known as “asconoid”, but this severely limits the size of the animal. The body structure is characterized by a stalk-like spongocoel surrounded by a single layer of choanocytes. If it is simply scaled up, the ratio of its volume to surface area increases, because surface increases as the square of length or width while volume increases proportionally to the cube. The amount of tissue that needs food and oxygen is determined by the volume, but the pumping capacity that supplies food and oxygen depends on the area covered by choanocytes. Asconoid sponges seldom exceed 1 mm (0.039 in) in diameter.[14]

Some sponges overcome this limitation by adopting the “syconoid” structure, in which the body wall is pleated. The inner pockets of the pleats are lined with choanocytes, which connect to the outer pockets of the pleats by ostia. This increase in the number of choanocytes and hence in pumping capacity enables syconoid sponges to grow up to a few centimeters in diameter.

The “leuconoid” pattern boosts pumping capacity further by filling the interior almost completely with mesohyl that contains a network of chambers lined with choanocytes and connected to each other and to the water intakes and outlet by tubes. Leuconid sponges grow to over 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter, and the fact that growth in any direction increases the number of choanocyte chambers enables them to take a wider range of forms, for example “encrusting” sponges whose shapes follow those of the surfaces to which they attach. All freshwater and most shallow-water marine sponges have leuconid bodies. The networks of water passages in glass sponges are similar to the leuconid structure.[14] In all three types of structure the cross-section area of the choanocyte-lined regions is much greater than that of the intake and outlet channels. This makes the flow slower near the choanocytes and thus makes it easier for them to trap food particles.[14] For example, in Leuconia, a small leuconoid sponge about 10 centimetres (3.9 in) tall and 1 centimetre (0.39 in) in diameter, water enters each of more than 80,000 intake canals at 6 cm per minute. However, because Leuconia has more than 2 million flagellated chambers whose combined diameter is much greater than that of the canals, water flow through chambers slows to 3.6 cm per hour, making it easy for choanocytes to capture food. All the water is expelled through a single osculum at about 8.5 cm per second, fast enough to carry waste products some distance away.